The Basic Sequence

As said in the introduction, modern MML's basic syntax derives from sheet music. It's not necessarily made to be read by performers such as ABC Notation or for full creation of sheet music like Lilypond, but many of its core elements are made having sheet music notation as its conception. So the best way to explain the basic syntax is with sheet music.

For those more familiar with trackers, which have a rigid visual timescale unlike sheet music, it can be useful to think of MML as taking the sequential values of a channel and removing the empty space between commands.

I'll see if I can make an explanation in the future that's easier for people who don't have a clue about sheet music.

Most of what's contained here is basically universal among all syntaxes. However, some of them might tackle things diferently, or some of them might not support one or two things. If you want to try things out as they're explained, please follow the PMD section up to the PMD MML's Structure, which is the format I'll be using for this explanation (write the sequences in channel G so it doesn't require additional setup; this is done by starting a line with G followed by some whitespace). But there shouldn't be any need as audio examples will also be provided.

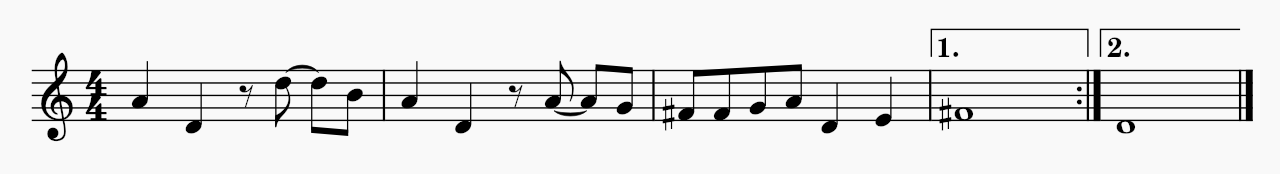

For this guide, we'll be using a familiar song as a basis.

Notes and Note Lengths

The usual notes are those standard across music:

a b c d e f g

Something to reinforce early is that MML is case-sensitive in most drivers. All notes must be typed in lowercase as to, for example, not be treated as a command that may use the capital letter.

Note lengths are specified by a number after the note. Similar to sheet music, they operate by dividing a whole note by that number. So:

1 = Whole note | 2 = Half Note | 4 = Quarter Note | 8 = Eigth Note | and so on...

The range of values you can input will vary depending on the driver and the tick count for the whole note. Since it works by dividing that number, you can also easily make triplets using multiples of 3.

From these two we can start transcribing the song above, starting with the two quarter notes for a and d:

a4d4

Now, we need a rest. For that we'll use the letter r. It works the same as a note, so you'll assign a length to it too, i.e. r8.

Let's continue:

a4d4r8d4b8 a4d4r8a4g8

Notice that in the first measure, I chose to type the second

dasd4instead of tying 2d8's. This is just because it would be redundant. One could use the tie command&and write it asd8&d8if desired.

For the next part we'll need a sharp f. For sharp and flat notes, we simply add a + or - after the note respectively. The note + sharp is treated as a note input by itself, so it's always before the length. So for an eighth note f sharp, this would be f+8.

a4d4r8d4b8 a4d4r8a4g8 f+8f+8g8a8d4e4 f+1

Notice how I used a space when the measure ended. Space may freely be used in the script as the result will be the same, for the most part. Each format will differ, as each disagrees about some specifics, but as a rule of thumb:

- Don't put space between numbers

- Don't put space before sharps/flats.

- Don't put space before dots.

- Don't put space before command values.

Spacing can greatly improve readability of your script. Personally, I like using spaces to limit a measure, or a beat in really fast sections. I also use it often when there are 2 parts playing the same rhythmic patterns. There's a huge variety of ways you can do it.

Before we wrap up this section, let's simplify the MML with one command: default note length (l<value>). This will set a default length value so that you don't have to keep typing the same value. It's good to anticipate which note will be the most frequent and set it as the default to save yourself time. In this case both 4 and 8 appear 8 times, so it's down to preference. I'll go with l4. This will mean removing the length after a note will make the length default to 4, a quarter note.

l4 adr8db8 adr8ag8 f+8f+8g8a8de f+1

Octaves

If you tried playing what we wrote, you probably noticed that a note is playing in the wrong octave. Let's fix that.

To set the current octave we use the o<value> command. This will change the current octave to a fixed one, and everything that comes after will use it as a basis (absolute change). Most drivers limit the range to 1-8 for simplicity's sake.

o4 l4 adr8db8 adr8ag8 f+8f+8g8a8de f+1

Usually o4 is set for the octave containing middle c, but it can vary.

We can also change the octave relative to the previous one with the < and > signs, which makes it easier for short changes (relative change). The default behavior is < decreases it and > increases. There are some exceptions, but usually, you can change this with a header.

o4 l4 adr8>d<b8 adr8ag8 f+8f+8g8a8de f+1

Loops

Ignore this part if you want to use AddMusicK.

Loops work similarly to how repetition works in sheet music, by setting a beginning, end, and an optional break for quitting it from the last time it's played.

For all MML formats, you set the start and end of a loop with [ ]. The basic syntax looks like this:

[ <sequence> <break> <sequence>]<number of repetitions>

The break symbol varies depending on the format. In PMD's case, it's :. The part after a break will play for every loop except the last.

Let's apply it to the song:

l4 [adr8>d<b8 adr8ag8 f+8f+8g8a8de : f+1]2 d1

This won't be needed for this song, but in most formats, you can nest as many loops as you want. That is, you can have as many loops inside of loops inside of loops—etc.—as you want. This can help save a lot of typing and space. If we wanted to play the whole thing twice, we could type:

l4 [[adr8>d<b8 adr8ag8 f+8f+8g8a8de : f+1]2 d1 ]2

How exactly the loops behave in regard to resetting commands and other settings depends on the driver, so I'll be sure to point out these differences on each's page. For example, PMD doesn't reset commands when looping, so if you type:

[cdefgb MP-80]2...theMPeffect (a rising/falling pitch) will be active the second time it plays.

Just to get finished with the basic sequences, there are 2 things that won't be needed for this song specifically, but are still common in basic sequences:

Ties/slurs

They are used both to change notes without completely starting a new note, and to extend the current note's length. In PMD, they're done with an &, but it's not uncommon for drivers to use ^ too.

Example 1:

c8 & d8 e4

Result: d will play without playing a new note. The result is a slur from c to d. The e is not slurred.

Example 2:

c8 c8 c8 & c8

Result: it's the same as a c4, with the two eighth notes tied.

When the goal is just to extend the note length, some drivers allow you to just add a length value instead of the note after the tie. The previous example can be rewritten in this way as c8 & 8. Others might have a different command specific for that (usually for saving space in compilation), but the ties will always allow for that.

Dotted Notes

By adding a . after the note or note length, it'll add half of its length, as a dotted note does in sheet music. Some drivers even allow you to stack them up, progressively adding halves as a quarter, then an eighth, a sixteenth, etc., but it's not very common.

Example:

l4 ad.>d<b8 ad.ag8

Result: the same as placing a tie with a d8 after, d4&d8.

Common Commands

This is an explanation on the most frequent sequence-related commands you'll find across all formats. All the examples will be done for PMD, but they'll apply to many others, at least in concept.

Title format for each section is Command Name (Common Representation if applicable). There may be multiple common representations.

These commands will affect everything that comes after it, requiring a reset to the previous value if one wishes to return to how it was previously.

Tempo ( T<value>,t<value> )

This sets the tempo of the song from that point forward. Most often, the value is the desired BPM itself, but sometimes it can be the internal timer.

Using + or - before the value turns it into a relative change.

Example:

l8 t150 cdefg t+20 cdefg

Result: will sound the same as:

l8 t150 cdefg t170 cdefg

Volume ( V<value>,v<value> )

This sets the volume of the current channel from that point forward. The value range will depend on the driver and/or soundchip.

Like tempo, more often than not you can change it relatively with + or -. Many drivers also use ( and ) for changing it relatively.

Example:

l8 v13 cdefg v10 cdefg v+3 cdefg ((( cdefg

Transposition/Modulation

Note: While "transposition" is the common term, "modulation" is used in some reference materials. They usually mean the same thing.

There are 2 main types of transposition commands: normal transposition and channel transposition.

Normal transposition will make it so everything placed after it will be transposed by the given number of semitones.

Example:

l8 cdefg _+2 cdefg

Result: it sounds the same as

l8 cdefg def+ga

Channel transposition behaves the same, but it'll include the relative transpositions without any conflict. Because of that, it's good to use it sparingly, and use the normal transposition instead until you want to transpose a whole song or section that already uses transposition commands in it.

Example:

l8 cdefg _M+2 cdefg _+2 cdefg

Result: it sounds the same as

l8 cdefg def+ga ef+g+ab

These commands are big time and typing savers, useful for playing the same line in other keys, or writing something in a key with less sharps or flats, thus having to type + or - less often.

Detune (D<value>>)

This will detune the current channel by a certain amount from that point forward.

Most often, this will change the value according to the soundchip's pitch range instead of by a more intuitive unit (such as cents), so how much true detune it amounts to will change depending on which point in the range you are. Usually, the higher the note is, the stronger the detune will be for the same amount.

l2 o2 D0 g D-2 g o6 D0 g D-2 g

Result: the second one is at higher range, so the detune change is much more noticeable.

Some drivers conpensate for this but it seems to be the exception rather than the rule.

Quantization ( Q<value>,q<value> )

Quantization in MML is used to automatically cut off notes within their original lengths. There are 2 possible ways of doing it (usually both are supported): corase and fine.

With the coarse setting, (in PMD, an upper case Q) it takes the note and only plays for the given number of eighths of its length. This works like a stacatto in musical notation, except you can specify how much of the note you want played.

Example:

l8 Q8 cdefg Q4 cdefg

Result: will only play half (4/8) of its length. After the Q4 command, it would be the same as if l16 crdrerfrgr was typed instead.

With the fine setting, (in PMD, a lower case q) it'll subtract the given number of ticks from the length of the note.

Example:

l8 q0 cdefg q1 cdefg

Result: the quantization makes the instrument release 1 tick before the next note, allowing for a very, very short rest.

As the example shows, the fine quantization is particularly useful in FM drivers, as it'll allow the envelope to reset in situations it wouldn't. The envelope describes an instrument's volume over time when it is played and stopped, so tiny changes in when a note is stopped can notably change how the instrument sounds between notes. It also can help emphasize any instrument's attack (the rise in volume when a note is first played) with the momentary silence right before the note, notably used in Megaman's NES soundtracks.

When there are ties/slurs, this command will account for the whole tied length, so:

l4 Q6 c&de

Will sound the same as

l4 Q8 c&d8r8e

Channel Loop ( L )

Channel loop sets the loop point of the current channel, meaning everything after it up to the end of the song will play in repeat endlessly. In most drivers this is set by the letter L.

L cdefg ;cdefg plays on repeat forever

This is done by channel, meaning if you want to have the whole song use that loop point you need to point it accordingly.

This also means you can loop them out of sync, which is usually a bad idea but can be used for making loops more interesting and whatnot. Nin-kuukuu used it for making a 40+ days long song.

Sequence Macros

Sequence macros are useful for saving time and typing, making the driver play the set sequence whenever it's called. There are many situations where they can be useful, including:

Setting many commands with a single one. This is really handy for making drums, which usually will take many commands at once.

Example:

!b @1 MP-80 v10 o1 _+9 Q4 \vh12 \b\h

!s @2 MP-40 v13 o4 _+7 Q8 \vh12\vs15\s\h

!H @4 *0 v12 o7 _0 Q8 \c

!h @5 *0 v10 o7 _0 Q4 \vh6\h

A l8 !b c !h c !s c !h c !b c c !s c !H c

The above example is a typical FM drum setting in PMD. Each macro (represented by ![character]) contains respectively:

- Change instrument (

@) - Set pitch fall (

MP), or turn it off (*0) - Volume (

v) - Set octave (

o) - Transpose (

_) - Quantization (

Q) - Play the corresponding rhythm channel (various commands starting with

\)

This allows these huge sequence of commands that would have to be set in every drum part to be summarized into their own singular commands, which will be applied to the note that comes after the macro in the sequence, making this kind of sequencing become much more simple.

They're also useful for playing repeated patterns which can be transposed with a command.

Example:

!a rgb>d [f+gf+d]3<

G l8 v15 @5 o4 !a !a _-5 !a !a

Result: the macro plays twice and then it plays twice again, but transposed down.

Among many other uses.

Most times, the sequence in a macro is added to the main sequence as is during compilation, so they'll operate like any normal sequence. Remember to keep track of what commands you're using in one, in case it results in any unintended change.

Very few drivers will have absolute macros, which are referenced, instead of added, within the sequence. This helps save space in the compiled file, but also limits the freedom you have with macros a bit, mainly when it comes to relative changes. Definitely use them for drums if your driver supports it, since the example setup above increases the file size drastically.